LAW & DISORDER / CIVILIZATION & DISCONTENTS

Anon on the run: How Commander X jumped bail

and fled to Canada

One fugitive's epic tale.

“You scared?” asks the fugitive in the camouflage pants as he sidles up to our pre-arranged meeting point in a small Canadian park. He wears sunglasses to hide his eyes and a broad-brimmed hat to hide his face. He scans the park perimeter for police. “Cuz I’m scared enough for both of us.”

It’s a dramatic introduction, but Christopher “Commander X” Doyon leads a dramatic life these days. He jumped bail and fled the US after the FBI arrested him in 2011 for bringing down a county government website—the only Anonymous-affiliated activist yet to take such a step. When I meet him months after his flight, he remains jumpy about getting caught. But Doyon has a story he wants to tell, and after he removes his hat, sunglasses, and backpack, he soon warms to the telling of it. It's the story of how, in Doyon's words, "the USA has become so tyrannical that a human rights/information activist would feel compelled to flee into exile and seek sanctuary in another country.”

And it goes like this.

Cease fire

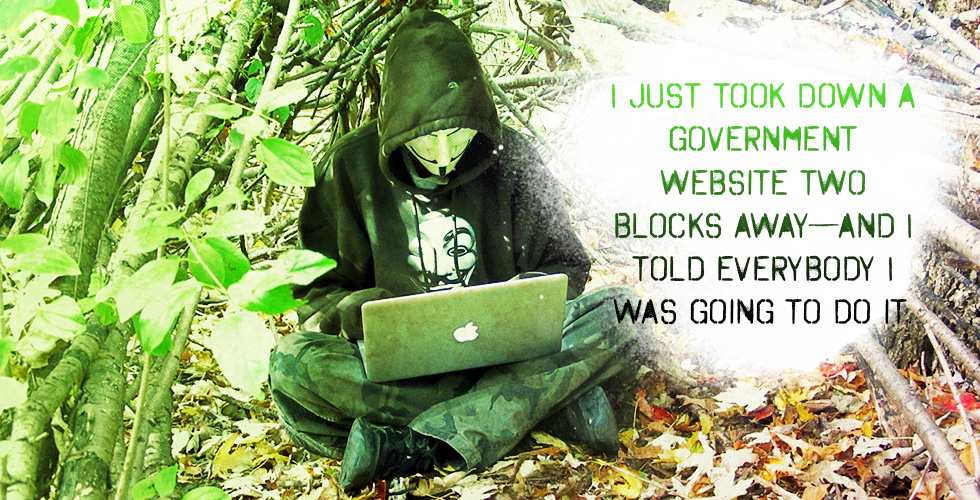

On December 16, 2010, at exactly 12:30pm, Doyon issued a typed order into an Internet Relay Chat (IRC) room used by the hacker collective Anonymous. "CEASE FIRE," it said in all caps. The command had no visible effect in the Starbucks where Doyon was working, though somewhere nearby the Web servers for Santa Cruz County, California groaned back to life after being flattened by a 30-minute distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack meant to protest an ordinance that regulated sleeping on public property.

Doyon unfocused his attention from his laptop screen and looked up at the coffee shop around him. Real life rushed back—the buzz of conversation, the smell of roasted beans. No one paid him any special attention, but Doyon felt a sudden pang of fear.

“It dawns on me… this isn’t Paypal or MasterCard,” he tells me when we meet in Canada. “This is fucking two blocks away. I just took down a government website two blocks away—and I told everybody I was going to do it. My heart starts to pound.”

He stepped out of the coffee shop and onto Pacific Avenue. Down the street, a reporter from local TV station KSBW was doing a “stand-up” with the Santa Cruz chief of police, asking the chief about the just-concluded denial of service attack. The chief was looking right at him.

He stepped out of the coffee shop and onto Pacific Avenue. Down the street, a reporter from local TV station KSBW was doing a “stand-up” with the Santa Cruz chief of police, asking the chief about the just-concluded denial of service attack. The chief was looking right at him.

So Doyon hopped a bus that took him into the mountains 20 miles outside of Santa Cruz proper, where he hiked up to the “pot camp” he called home for the moment. He stayed in the camp for a full week, scared of pursuit, until he was eating crusts of bread. The winter weather turned cold and wet, and Doyon grew miserable and hungry. He returned from the mountains to his old haunts in town and eventually to his regular coffee shops—despite knowing this “was a bad fucking idea.” He had reason to worry; over the last decade, by his own admission, he has done nothing but cause trouble in Santa Cruz. The cops knew him well.

One day in mid January, Doyon dropped by a favorite coffee shop, sat down, and opened his laptop. The barista was acting odd, giving a strange jerk of his head that made Doyon wonder if the man had a tic in his neck. Doyon logged into his password-protected computer and had just started work on the "operations" that take up most of his time when “a fucking arm comes from fucking behind me” and snatches his laptop by its screen. Doyon looked up to find a local cop holding his machine. The sudden realization of what happened hit him hard.

“I’m fucked,” Doyon says, remembering the moment. “They got the computer running.”

On screen, his documents were open for anyone to read: the press release announcing the attack, the Anonymous chat logs used to coordinate it, the High Orbit Ion Cannon (HOIC) computer attack tool. Out from the back room came a couple of FBI cybercrime agents in their “scruffy-ass fucking hoodies” and blue jeans. Doyon, one of the 40 Anons raided that day in a major sweep across the country, was served with a search warrant. In a press release announcing the raids, the FBI reminded people that "facilitating or conducting a DDoS attack is illegal."

Doyon wasn't immediately arrested on the DDoS charge, but he knew that a net was closing around him. He returned to his mountain camp and “smoked some fucking weed” before considering his options. The feds had all the data they needed to tie him to the Santa Cruz County attack, and he knew that federal charges were serious—"intentional damage to a protected computer” under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is punishable by up to 10 years in prison and a fine of $250,000. “Conspiracy” to attack a protected computer could add another five years. All that Santa Cruz County would have to show was that Doyon had caused $5,000 in damage (in the end, the county came up with a figure of $6,300), and he could be looking at years in prison. For someone who had lived outdoors for years, the thought of long-term confinement was intolerable. Doyon decided to run.

Within 48 hours, he had stowed his belongings in his mountain pack, hiked down the ridgeline from his camp until he struck Route 1, and hitchhiked north to San Francisco. He “ran in circles around the Bay Area” for a few months, moving from Berkeley to San Francisco proper to Silicon Valley cities like Mountain View. Doyon claims that a source within the FBI’s cybercrime division got in touch and warned him that a grand jury had issued an indictment and that an arrest was imminent. (The FBI did not respond to our requests for comment on these claims.)

So Doyon hopped a Greyhound bus to Helena, Montana. He planned to cross the unfenced Canadian border, taking up a new life as a fugitive. Such decisions aren’t made lightly. “When any person makes the weighty decision to leave their homeland and enter political exile they would be naïve to not accept the fact that they may never be able to go home,” Doyon says, reflecting on his experience. “Have I accepted this fact? Yes. Am I at peace with it? No, the pain of missing my loved ones and my home is with me every day. I don't expect it will ever be different.”

But first, he had to actually cross the border, a long hike through the wilderness. And although Doyon counted on plenty of hardships along the way, his first attempt at crossing to Canada brought a novel one: grizzly bears.

Attack and retreat

Doyon, now in his early 50s, grew up in a rural part of Maine, spending days or even weeks alone in the woods during summer vacations. He had seen plenty of small black bears and knew that even a BB gun could scare them off. While the forests and mountains of the Northwest held grizzlies, Doyon didn’t expect them to pose thatmuch more of a challenge.

The National Forest Service had a different view. After hitchhiking from Helena to Bonners Ferry, Idaho, Doyon crossed back into Montana in order to strike Kootenai National Forest. His research told him the national forest route was safer than simply hiking north from Bonners Ferry, since the Idaho land was private property all the way to the Canadian border. “If you know anything about Idaho, then you know they don't much like trespassers,” he says.

But the rangers at Kootenai weren’t keen on him entering their territory, either.

“I tried to walk through the front gate and the warden of the park wouldn’t let me in,” Doyon said. “I was like, ‘Why?’ and he’s like, ‘You gotta buy bear spray.’ And I was like, ‘No big deal’—I was figuring it was like a little can of Raid or something like that, right? Fucking thing is the size of a fire extinguisher and costs a hundred and fifty bucks. I was like, ‘That’s bear spray? You ain’t got a smaller size than that?’ He was like, ‘Dude, you don’t want a smaller size than that.’”

“Bear spray” is simply a form of pepper spray, generally a two percent capsaicin solution that can reach up to 30 feet away. It can help scare off a bear, but it doesn’t always work. “There have been cases where bear spray apparently repelled aggressive or attacking bears and accounts where it has not worked as well as expected,” warns the government. Outfitter REI has its own, blunter warning: “Use with extreme caution—if not used properly, it can disable the user rather than the bear.”

Undeterred, Doyon left the ranger station without the spray, hiked three miles up the road, and “just jumped the fence.” He set out for Canada, using a small GPS unit to track his progress, walking alone through the backcountry with all of his worldly possessions in his pack. The goal was to make it to Canada’s route 59, south of a town called Creston, where Doyon had arranged for a sympathizer to pick him up. As the sun dropped below the western mountains, Doyon made camp, burrowed into his sleeping bag, and went to sleep.

He woke to the sound of snuffling. Attracted by the scent of Doyon’s food, a grizzly bear had lumbered into camp in the middle of the night.

“I came out of the tent and this thing goes right up on its fucking hind legs,” says Doyon, performing quite a credible impression of a roaring bear. “I got fucking piss running down my leg and shit. I just ran like hell.”

He later crept back to camp and found the bear had left, but not before eating or spoiling much of his food. Doyon gathered the salvageable food and gear, stuffed it back into his pack, and decided to make one more attempt to reach Canada. When the sun rose, he hiked north again but spent the entire day slogging through a few miles of tough backcountry. As night fell on the second day, Doyon made camp again, went to sleep again, and woke again to another bear. This time, the animal wrecked his laptop.

“That’s fucking it,” he concluded. “Fuck this shit.”

He trekked out of the park and hitchhiked back down to Helena, where he caught a Greyhound back to California. 72 hours after facing his second grizzly, Doyon stepped off the bus in San Francisco. It was May 2011. He remained a wanted man.

Meet Commander X

In the early 1980s, when Doyon was in his early 20s, he had moved down the coast from rural Maine to Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the time, it was a “tripping fucking city to live in” where Doyon dropped plenty of acid, smoked plenty of weed, and found a political movement agitating against apartheid in South Africa. The mix of Grateful Dead culture and a righteous indignation intoxicated Doyon, who was soon recruited into a small group called the People’s Liberation Front (PLF), which he describes as “one of the most secret organizations in the world.” The PLF was led by an older man with slate grey hair who favored aviator sunglasses and bomber jackets and who went by the name "Commander Adama." Adama had already recruited five or six young people to join his quest for justice, and Doyon soon decided to help the cause. The group traveled from protest to protest performing technical services—printing flyers, deploying backpack FM radios for communications, surveillance.

When Adama later asked his recruits to relocate with him to California, Doyon and three others followed. They spent the next few years traveling around the Northwest in a van, helping groups like the Animal Liberation Front release animals. “We would sneak up basically in the middle of the night on mink farms and free all these little animals,” Doyon tells me, though his memory of those days is fading a bit. “And I believe we burned a couple [of buildings] to the ground. They weren’t mink farms that we burned… the fuck did we burn? I think it was a lumberyard, or… fuck. I can’t remember now. There were a couple places that we set fires.”

When Adama later asked his recruits to relocate with him to California, Doyon and three others followed. They spent the next few years traveling around the Northwest in a van, helping groups like the Animal Liberation Front release animals. “We would sneak up basically in the middle of the night on mink farms and free all these little animals,” Doyon tells me, though his memory of those days is fading a bit. “And I believe we burned a couple [of buildings] to the ground. They weren’t mink farms that we burned… the fuck did we burn? I think it was a lumberyard, or… fuck. I can’t remember now. There were a couple places that we set fires.”

The PLF stayed in the background and, because groups that live in the darkness generally prefer not to use real names, Doyon needed his own nom de guerre. He quite consciously set out to pick a something “impressive.” For two weeks he jotted names on scraps of paper but found nothing he liked. The came the breakthrough: what about a single character? Most letters felt ridiculous (“Who wants to be G?” Doyon says), but X seemed promising. Doyon jumped online and spent the next four days scouring BBSes for anyone else using X as a handle. No one had it, so Doyon took it.

Commander Adama created the PLF as a hierarchical organization, the opposite of Anonymous, with a Supreme Commander at the top and the rank and file—which never numbered more than 12—taking orders. From 1985 to 1995, Doyon was known simply as X. In 1995, as the group moved from supporting direct action to information disclosure and the Internet, Doyon was offered rank within the PLF. He became “Commander X” and helped the organization emerge from its secrecy to become a self-described “cyber militia” that welcomed members from all over the world. In 2007, the group allied itself with Anonymous; Doyon soon became so active that, when HBGary Federal CEO Aaron Barr attempted to ID the leaders of Anonymous in early 2011, he named Commander X as one of the top three.

Rather than bringing down Commander X, however, Barr’s work gave him the additional strength of notoriety. The Anons who hung out in the group’s IRC channels now all knew who he was, and the Commander X persona became increasingly central to his identity. Within Anonymous, critics carped that Commander X should stay a bit more anonymous, rather than popping up all the time to give interviews such as the one in which he told journalist Dan Tynan that “Commander X is a cartoon character that inspires thousands.”

But Doyon refused to retreat back into the shadows because, he says, the Commander X persona was simply too inspiring to others. Not that being such a figure is easy, though.

“All the costs are personal and all the benefits are helping people,” he says. “It’s a huge fucking burden on my ass.”

Arrest

On September 21, 2011, racked with the shakes and burning with fever, “so sick that I could barely fucking walk,” Doyon lay outdoors in his sleeping bag just a few miles from the Googleplex. He had no diagnosis, but he did have a fear. Multiple sclerosis ran in his family and he had seen the disease work against his sister. (In retrospect, he believes it was a blood infection instead.)

He slipped into a vision so intense he still can’t say if he was dreaming or hallucinating. In it, he ran through the rooms of a large house, an unnamed horror chasing him down. He could find no exit. Instead he ran in circles, the same rooms coming around again and again as the thing stalked him through darkened halls.

He woke ill and exhausted on the morning of September 22—“this close to fucking dead”—and felt the weight of premonition settle onto him once more. He had felt it often in the last months as he raced around the Bay area one step ahead of the FBI agents hunting him down. A few weeks earlier, for instance, he was sitting in Coffee to the People on San Francisco’s Haight Street when a pair of FBI agents walked in and asked the barista if the coffee shop had a wireless router in the back room. Judging by their appearance—big guys in immaculate black suits and patent leather shoes—these were Special Agents, not the more technically trained cybercrime agents who might be better equipped to catch him. Doyon’s heart pounded as the agents took a seat at the table next to him.

He had at that moment been working on a press release for Anonymous’ Op Orlando, supporting the group Food Not Bombs in its struggle to conduct mass public feedings despite a local law limiting the group to two such events per year. Doyon had also coordinated denial of service attacks on the City of Orlando’s website in a show of support for Food Not Bombs—but the attacks failed. “The site was too well defended,” hetold the Orlando Weekly at the time. “Apparently the City of Orlando expected us.”

In that interview, Doyon admitted he was shutting down free speech in the name of free speech, but he defended the tactic as “no different than taking up seats at the Woolworths lunch counter.” Food Not Bombs didn’t want this kind of help; it condemned the online attacks. But Doyon said he needed no one’s permission to agitate on the side of “the people.”

In the Haight Street coffee shop, Doyon closed the lid of his laptop and picked up the “I need food” cardboard sign he used to raise cash, then worked his way around the FBI agents in order to get to the door.

Such incidents piled up. A few weeks later, at a Berkeley coffee shop, Doyon sat at a table when another FBI agent walked in with paperwork authorizing him to remove and search the shop’s wireless router. A moment after the agent stepped into the back of the shop, the Wi-Fi went down. Again, Doyon edged out the door, convinced agents were trying to sniff out his digital trail.

He continued to run throughout the summer and into the fall, and though it was bad for him personally, it was a heady time for Anonymous. The splinter group of hackers called Lulzsec had been on a rampage, garnering worldwide headlines. Doyon claimed to be the moving force behind Op BART, the Anonymous-led protests against San Francisco’s subway system that had cut off cell phone access to stations in anticipation of protests. He continued to work on ops related to the Arab Spring—black fax bombs targeting Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, e-mail hacks, DDoS attacks. Life became a blur. Doyon worked all day at coffee shops and crept away to parks to sleep for four hours at night before waking to do it all again. A pair of PLF members helped to shuttle him around the Bay area so that he never became a sitting target. His work had meaning and, if you accept the contested premise that Anonymous and the PLF were having real effects in Arab states, global import.

“If I could have kept the pace up, I don’t think they ever would have caught me and would eventually have given up,” Doyon says of the FBI, believing it would cost the agency too much money to hunt him intensively for long.

But his pace began to slow. By mid-September, he could run no more. Increasingly ill, he made it down to Mountain View but became too sick to relocate again. A week into his illness, Doyon began to see more Crown Vics—the cop car of choice—and he feared his FBI pursuers had tracked him to the area. His fever rose. He lay in his camp for several days straight, logging into the free public Wi-Fi network that Google built and maintains throughout Mountain View. His judgment impaired by illness, Doyon ventured back into town on September 21. He called Jay Leiderman, a lawyer from downstate Ventura who agreed to represent Doyon pro bono, and warned him an arrest might be near. Leiderman agreed to fly up to Mountain View and meet Doyon the next day at his favorite coffee shop in town.

That afternoon, Doyon had an IRC chat with another hacker known as Locke. Locke, a student, offered to wire Doyon some cash through Western Union. Doyon provided him with the address of the coffee shop. It wasn’t a wise move for a man on the run, but Doyon was worn down by illness and fatigue and by the constant running. Fearing the feds might grab him soon, Doyon gave the “keys to the kingdom”—such as his Twitter account password—to his subordinates in the PLF that evening. He then says he used an encrypted, one-time only e-mail service to send a message to the FBI’s cybercrime division. “I am not armed,” it said.

After the hallucinatory night, Doyon roused himself again and returned to the coffee shop in time for his meeting with Leiderman. At 9:00am, from the second floor of the shop, Doyon looked out the window and saw a pair of Crown Vics in the street below. “This is it,” he thought, a sudden shock of sweat running down his back. “They’re here for me.”

Doyon bolted for the back stairway, thumped down the steps and out a side door, emerging into an alley. A blue Crown Vic with agents wearing FBI windbreakers shot past on the street; Doyon limped for one of the alley’s exits. When he looked back over his shoulder, he saw the car’s brake lights snap on. He had been spotted.

Doyon made his way to the street running past the coffee shop’s main door and saw an enclosed bus kiosk. With nowhere else to go, he stepped inside the kiosk and squatted down. He lit a cigarette butt. The blue Crown Vic roared up, jumping up onto the curb. “People are literally leaping out of the way of this fucking cruiser,” Doyon says, describing the moment. Agents swarmed to the bus stop. Doyon likes to believe his e-mail to the cybercrime division led them to tone down their posture.

The lead agent—which according to court documents was Special Agent Adam Reynolds—stepped into the bus stop as Doyon smoked the end of his cigarette. He put Doyon in handcuffs and searched his pack, then asked, “Are you ready?” before bundling him into the car for processing. Doyon, who has a reflexive dislike of all things police and calls the US government “one of the world's worst tyrannies,” admits he was handled well. No body tackles were used to subdue him, no tasers or pepper spray. (Reynolds did not respond to questions about the details of Doyon's arrest.)

“I would almost go so far as to say they were gentle with me,” he admitted.

Shortly after Doyon had been taken away, his lawyer arrived, looking for his client.

Righteous hacktivists

Jay Leiderman's phone rang as he pulled up to the Mountain View coffee shop in a rental car. His secretary was on the line saying that Doyon had just been arrested by the FBI and would soon be arraigned at federal court in San Jose. Leiderman hopped back into the car. He hadn’t come prepared for a federal court appearance and only had jeans and sneakers. He made his way to San Jose by noon and learned that his client wasn’t scheduled to appear before a judge until 1:30pm He asked the security guys running the metal detector at the courthouse entrance where he could get a suit quickly. They recommended a Vietnamese tailor down the street.

“I’m usually an Armani guy if I can be, but I went from jeans into the one of the nicest $99 suits I had seen, plus a tie, pocket square, and socks,” says Leiderman. “I got the shoes and belt at a Ross [Dress for Less store] in between the tailor and the courthouse. The guys that worked security were impressed.”

“I’m usually an Armani guy if I can be, but I went from jeans into the one of the nicest $99 suits I had seen, plus a tie, pocket square, and socks,” says Leiderman. “I got the shoes and belt at a Ross [Dress for Less store] in between the tailor and the courthouse. The guys that worked security were impressed.”

Leiderman had involved himself with Anonymous after watching the Lulzsec crew wreak mayhem that summer. “Oh shit, someone here is going to really need a lawyer,” he began thinking. He “floated a tweet out there” during the early summer, offering pro bono work to “righteous hacktivists.” He heard from many Anons, including Commander X—whose name he recognized from Ars Technica’s reporting on the HBGary story—and had to pick one. He chose Doyon.

Now he was in San Jose, in a new suit and shoes, defending Doyon over a 30-minute DDoS attack. Leiderman made the 1:30pm court appearance, at which Doyon entered a plea of “not guilty.” A week later, Doyon was out of jail on a $35,000 signature bond in the name of labor lawyer Ed Frey, who had protested Santa Cruz’s no-sleeping policy with Doyon and had a long history of such battles. Should Doyon not show up for a court date, Frey would suddenly owe a huge amount of money.

Doyon’s bail was not unrestricted, however, and those restrictions would eventually lead him to take up a fugitive’s life once more. The court forbade Doyon from using Twitter. Or Facebook. Or IRC. Or from communicating with other Anons. Or the PLF. In other words, the very activities that occupied most of Doyon’s time were off limits.

“I’m not saying we’re in a police state,” Leiderman says when talking about the restrictions, “but it sure looks like it when you evaluate the system of pretrial release. His human contact is not really human contact—he does his life’s work through IRC.”

Leiderman worked on Doyon’s case for the next few months as it jerked along through the justice system and soon believed that Doyon could beat the rap. The CFAA, the law under which Doyon was charged, has long been criticized as fatally overbroad; Leiderman shares those concerns. “It’s both on its face an overreaching law and it’s being used in an overreaching way,” he says.

But Leiderman was convinced he could limbo under the CFAA’s low bar to prosecution by knocking $1,300 off the $6,300 damage claim from Santa Cruz County. Much of the damage appeared to be charges for non-overtime employee salaries—salaries already paid by the state, rather than new expenses. Such a win could also make a larger argument of Leiderman’s: DDoS attacks cause little damage and should be treated as political protest.

“They didn’t harm Santa Cruz’s computers, they didn’t go in and rape their servers,” Leiderman says of Doyon and crew. In his view, the DDoS was “absolute speech under the First Amendment.”

He soon began to worry he wouldn’t have a chance to make the argument, however. Anonymous tips warned him that Doyon—fed up with not being able to operate online as he liked—was thinking about fleeing to Canada. Doyon stopped answering Leiderman’s calls and e-mails. When Leiderman showed up to court in San Jose for a status hearing on February 2, 2012, his client did not appear.

“So, returning to Mr. Doyon,” said the government’s lawyer, according to a court transcript, “his appearance has not been waived. He is not present here. And so I’m inquiring as to whether there’s a reason for that.”

Leiderman knew nothing. The judge issued a bench warrant for Doyon’s arrest but agreed to hold it for two weeks.

On February 16, everyone reconvened in the same San Jose courtroom. Doyon was still missing. “It appears as though the defendant has fled,” said the prosecutor. The judge looked around the courtroom and said he saw no sign that Doyon was going to appear. The prosecutor noted they actually had good reason to believe Doyon would not appear—on February 11, Doyon had issued a press release titled “Commander X escapes into exile.”

Doyon was gone, Ed Frey owed the court $35,000, and Jay Leiderman’s “DDoS as free speech” test case just lost its client.

“A charming feeling as an attorney,” was how Leiderman described the moment to me. “Dateless on prom night.”

Into the woods

Unwilling to be pushed out of activism for two years while the case progressed, Doyon began planning to leave the US—though there was that little matter of Ed Frey’s $35,000 signature bond. The two men met back in 2010 during “Peace Camp 2010,” a protest against the Santa Cruz no-sleeping law in which activists eventually slept together on the county courthouse steps for weeks.

Doyon had a way with words and could be counted on for a good soundbite, such as when he said that fight over the law was “a fight about aesthetics. One man's garbage is another man's belongings. I think millionaires are unaesthetic; I think Hummers are disgusting. You see the ridiculousness. This is class warfare.” Frey had a long history of similar activism and befriended Doyon during the protests.

Doyon went to Frey around Christmas 2011 and told him that he might need to leave. “His last words in the discussion to me were, and I quote, ‘Don't worry about the money. It doesn't matter. Do NOT make your decision with any consideration of that,’” Doyon says. (After Doyon left, Frey told Talking Points Memo, “I’m a lawyer, but I don’t have a lot of money. But I did sign the bond for him, so they’re going to come after me for it. The best I can do for them would be monthly payments, I guess.”)

Doyon spent January 2012 plotting border crossing routes for hours using Google Earth, eventually settling on one that crossed from Washington state into British Columbia. Unlike his first, solo attempt, he had help this time in the form of “Op Xport”—an Anonymous/Occupy-run underground railroad. Doyon became “the package.” He put himself under the command of a manager who coordinated the ten people, four safe houses, and three drivers used to ferry Doyon from the Bay area north to Seattle.

In early February, the owners of Doyon's final safe house in Seattle drove him out into the wilderness. “I was dropped off where the trees began, which was approximately five miles from the border at approximately midnight,” Doyon says, “and I had to jog across a farmer’s field to get to the tree line. The hazards were primarily caused by stuff you can't see on a satellite view on Google Earth. For instance, immediately upon entering the tree line I was confronted by a 12-foot wall of thorn bushes nearly 50 feet deep. Unfortunately, a machete was not one of the items in my kit.”

The route turned out to be far rougher than anticipated, and the projected two-day hike stretched to four. Fresh water became a problem. But Doyon made it across the border eventually and straggled out of the wilderness and into the nearest town. The first Canadian he saw was a barista, of course.

“PLF Central Command” then issued the press release announcing Doyon’s safe crossing. It thanked the Occupy and Anonymous movements “for the great care they took with the first person to utilize it to seek freedom from the tyranny of the USA.” It demanded that the Anons arrested for the DDoS of Paypal be released with an apology for “harassing these courageous human rights and information activists.” And it “reminded” Canada of its “decades long and noble tradition of harboring American political dissidents during times of great tyranny in the USA.”

When we meet, I ask Doyon why, as a fugitive, he decided to telegraph his location this way. “That goes to one of the primary reasons I made the choice to go into exile in the first place,” he answers without hesitation, “and that is to highlight to the world the political nature of these prosecution/persecutions."

And yet Doyon agrees with the FBI that he should not have been allowed to organize a DDoS attack on the Santa Cruz County website; he simply believes that the penalty should be more proportional to the crime. Doyon says he would return to the US tomorrow if the government offered him time served plus a $250 fine—the same penalty most of his real-world sit-ins earn.

The storyteller

Did it all happen exactly this way? I start wondering when, during our day together, Doyon tells me that he misled a German reporter who had ventured across the Atlantic to meet him. The deception involved just how much firepower Anonymous commanded back when it was attacking sites like PayPal in late 2010. The group’s mythology painted itself as an unstoppable force of millions of users, rising spontaneously to confront corporate and governmental oppression. While there were many Anons present at key moments, numbers could fall well short of the propaganda most other times—and that meant there simply weren’t Anons running DDoS tools off their home computers to get the job done. When that happened, top Anons might bring their private botnets into play.

Doyon says that PLF controlled an “ethical botnet” of 50 servers the group had outfitted with hundreds of virtual machines, each running a copy of the Low Orbit Ion Cannon (LOIC) data flood tool. When Anonymous began its attack on Paypal, the central LOIC “hive” didn’t contain enough users to bring down Paypal’s site, and some of the Anons with access to private botnets were AWOL. So Doyon “kind of came to the rescue that day” by using his own botnet in the attack, he says. As we talk, Doyon chides another Anon who would “never quite embrace the idea that we needed to cheat to get it done.”

But earlier this year, when Stern magazine journalist Joachim Reinhart asked Doyon point blank if botnets had been used in the operation, Doyon told him that botnets weren’t needed; there had been enough grassroots Anon firepower. “I’m not a liar and I didn’t lie to him, but I didn’t cop to it, either,” is how he describes this answer to me. Nevertheless, it makes me wonder about details in the story Doyon is telling me, too.

I contacted Kootenai National Forest and asked them about Doyon’s account of being turned back by a ranger for lacking a $150 canister of bear spray. A park employee told me that “the Kootenai is a national forest, not a national park, so we don't have staffed entrances or exits anywhere. Anyone can come and go in the forest whenever they please and there are no fee stations so it would be unlikely he would have been stopped by a ranger unless he was doing something suspicious. We recommend that people carry bear spray if they will be visiting certain parts of the forest, but we don't require it and we don't sell it at any of our ranger districts. Also, bear spray typically costs between $30 and $50, not $150.”

When I ask Doyon about the discrepancy, he says his recollection differs. He approached the park’s main entrance, where he was “told that hikers had to register and carry bear spray. I left, walked down the road a half mile and cut diagonally through a field into the park and avoided the marked trails.”

When I ask Doyon about the discrepancy, he says his recollection differs. He approached the park’s main entrance, where he was “told that hikers had to register and carry bear spray. I left, walked down the road a half mile and cut diagonally through a field into the park and avoided the marked trails.”

This is more sedate than the initial version of events. As for the claim that he was “this close to fucking dead” when arrested, I asked Jay Leiderman how Doyon looked when the two met that day. Doyon was thin and ragged, with a few bruises and discomfort from the handcuffs, but “he lives a rough life, so he’s often in rough shape,” Leiderman says. “He was overall pretty much the same.”

It becomes clear as we talk that Doyon has a storyteller’s sense of the dramatic and a penchant for the Big Statement. PLF operations, for instance, tend to be grandiose. “Operation Freedom Star,” launched earlier this year, created the “PLF Space Command,” and sought a million dollars in donations to buy up an old satellite in order to provide broadband access to underserved parts of the globe. “Op Syria” aimed to “launch a major new offensive against the forces of tyranny and evil”; its status is currently listed as “success.” 2011’s “Operation USA” was said to be the beginning of “the Transnational Global Cyber Insurgency. Welcome to the second American Revolution!”

The pattern carries over into conversations with journalists. In May, Doyon famously told a Montreal journalist, “Right now we have access to every classified database in the US government. It’s a matter of when we leak the contents of those databases, not if… There’s a really good argument at this point that we might well be the most powerful organization on Earth.”

When I press him on this, the explanation is far more reasonable: Anonymous has received several terabytes of leaked data that appears to originate from US government databases, but it remains unclear whether this is of any real value. Doyon also insists that many of the geeks guarding these databases for the US government have come to Anonymous and pledged their support. “The simple fact is that by becoming one of the world’s worst tyrannies, the USA government has lost the loyalty and trust of many of the very people tasked with keeping their secrets safe,” Doyon says. After an obscure soldier like Bradley Manning could leak huge troves of US diplomatic cables, this statement isn’t as outlandish at it might have once appeared. On the other hand, the promised major leaks haven’t materialized.

Even some of the Anons with whom Doyon worked thought him too dramatic—and this from a group that thrived on drama. Sabu, one of the few Anon hackers with serious technical skills, called Doyon a “leaderfag” in chatroom transcripts—someone in love with the idea of being in charge. After Doyon fled to Canada, Sabu had even less complimentary things to say about him:

Sabu was later outed as a hacker-turned-federal-snitch, so it’s possible these are the views of his controllers rather than his own. But the enmity between the Sabu’s clique and Doyon ran deep, and the sentiment might well be authentic.

Jennifer Emick, a one-time Anon who has since turned on the group and who was the first to publicly identify Sabu by his real name, has spent the last few years tracking many of the players in the movement. She has little positive to say about any of them, but she reserves special scorn for Doyon. (The feeling is mutual.)

“He’s been a 'key player' in his own mind,” she says when I ask about Doyon’s influence. “I never saw that his PLF had more than a few dozen active members at any given time and maybe five or six loyal groupie types. Of those, he accused at least three of snitching on him… Honestly, in 2011, nobody cared about him at all. Anons thought he was a pretentious theatrical idiot.”

The life of a leader

But on the run in Canada, Doyon’s lifestyle is anything but pretentious. After smoking a cigarette to calm down from the stress of our initial meeting, Doyon takes me into the woods to show me an old campsite he built when he first arrived in the city where we meet. It looks like a skeletal beaver dam, interlocking sticks that form a support for a tarp at night. Returning to a sunlit clearing, he points to an abandoned warehouse where he can sneak inside to bed down in cold weather. The property’s security guard does nothing more than pull up in his car once a night before driving away and the building still has power for charging Doyon’s laptop each night. But it’s hardly the sort of place most people would choose to live.

Each morning, Doyon panhandles for cash until he reaches the $15 he needs. He subsists on coffee and cigarettes to make it through each day, then orders a large meal from McDonald's each night. For 10 hours or more a day, he is online from places like the local Tim Horton’s donut shop.

“Just setting up my computer so I can begin work is a 20 minute process due to the extreme security measures I use to avoid being tracked online,” he says. “All of my communications channels such as my many e-mail accounts, Twitter, Skype, and IRC, etc. need to be painstakingly opened based upon a rigid security protocol.”

Doyon then sets about his chosen work. Here’s how he describes the beginning of each day:

The work, entirely self-directed, takes place entirely online. The life of a homeless hacker can be a lonely one; Doyon says he has limited even those electronic communications with friends and family members back in the US. “Out of an abundance of caution, and to prevent the FBI from using them against me—I have severed completely all contact with them,” he says. “For me personally, this has been the biggest sacrifice connected to my choosing exile. Not a day goes by that my heart doesn't ache for those I love and miss so much.”

Why pay such a price? For Doyon, the answer is simple: activism is his life’s work and trumps all else. “I would hope people would see me as someone who dedicated their life to bringing freedom and justice into the world, and to giving a voice to the disenfranchised masses.”

That work has led him to a curious place. “All power is corrupt,” he tells me when explaining why he believes it legitimate to engage in vigilante corporate hacking. “All of it, dude.” Yet Doyon claims to have power—“we can come out of the wires like a goddamned fucking ghost and take your fucking shit.” When I ask whether it corrupts him as well, he says that spends plenty of time considering the question but that his primary goal is bringing his career as an activist to end in such way as to preserve the PLF. “This is my biggest challenge as the Supreme Commander of the Peoples Liberation Front—and one that I intend to fulfill with all the intelligence and thoughtfulness at my disposal,” he says.

The end of his Canadian odyssey remains unclear. He hopes to obtain political asylum from some country and notes that he has “people in Haiti and Ivory Coast and South America and the Middle East writing me saying, ‘Come start a revolution in our country!’”—but no offers have yet been forthcoming. After our meeting, a Canadian Anon finally offered to take Doyon in, putting a roof over his head and providing a bit of companionship as the harsh Canadian winter sets in.

It’s no long-term solution—and it can’t still the nightmares. In the Canadian dark each night, Doyon finds himself pursued through houses and across landscapes by shadowy figures. In the dream’s newest variant, Doyon walks through a nightmare city as an earthquake crumbles the buildings around him. He snatches people from the falling rubble, directing them to “run north” to safety.

It doesn’t take a psychologist to suspect that being a fugitive has left its mark. To Doyon, the constant dreams feel like a “symptom of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] from having been chased by the feds for most of the past two years.” Either that or “maybe I am just nuts.”

A question of perspective

At McDonald’s after a long day together, I buy cheeseburgers for Doyon. He steps away to the restroom and the young man ringing up our order leans forward slightly to murmur, “That’s a very nice thing you’re doing, sir. Can I offer you a free drink?”

I’m startled for a moment—after five hours of listening to someone tell you how “my fucking crew” stole Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad’s e-mails, it’s a jolt to one’s frame of reference to remember that society sees him as a bum—and decline the offer.

Because whatever else Doyon might be, he is not someone looking for pity. His hard road, whatever its worth, is a chosen road. While walking it, Doyon has embraced contradictions: he is an anarchist running a hierarchical organization, a worldwide activist whose office is local coffee shops, a proponent of radical disclosure who operates from the shadows.

He is Supreme Commander of the PLF, scourge of tyrants, a voice for Anonymous, a man behind a mask, a cyber knight tilting his lance on behalf of the downtrodden—or he is a hyperbolic homeless hacker in love with the overwrought tones of his own press releases, a quote machine for journalists, a grown man playing at grand titles and in love with secret societies.

But in either case, he remains Commander X.

No comments:

Post a Comment